Most foreigners have little to no knowledge of Japan’s original native religion. A religion based on spirits in all of nature itself.

Defining Shinto

Shinto is a Japanese religious tradition. Historians of religion classify it as an Eastern Asian religion, yet it is commonly referred to as Japan’s native religion and a religion-based in nature by its followers. Scholars refer to its supporters as Shintoists, but they rarely use that name themselves.

Not governed by a central authority, and its practitioners are quite diverse. Shinto itself is polytheistic defined as the belief in or worship of more than one god, unlike the Judeo-Christian belief of one God only.

The Japanese believe all things are said to possess a spirit or perhaps something like a soul as known in western cultures.

Shinto is a polytheistic religion centered on the kami (“gods” or “spirits”), supernatural beings who are said to inhabit everything, from a stone to an animal. Shinto is regarded as animistic (meaning all objects even nonliving things may possess a spirit) and pantheistic (meaning multiple gods).

Shrines are seen in a myriad of locations across Japan and sizes can range from a few feet across to massive complexes.

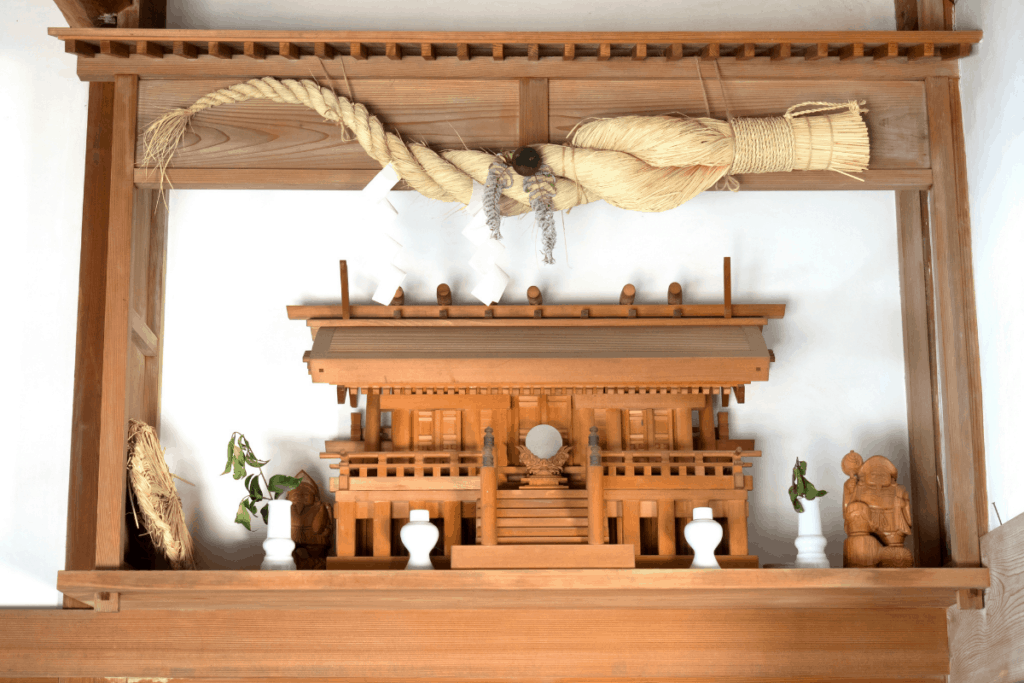

kamidana are home shrines or family shrines, and jinja are public shrines, where the numerous gods are worshipped and prayed to. The jinja shrines are staffed by kannushi priests who supervise offerings to the unique kami stipulated at that shrine.

Each large public shrine may have a set of matsuri or festivals throughout the year and practitioners are many.

Origins And Shinto Shrines

Kagura dances, rites of passage, and festivals are all traditional events at each shrine. Religious items, such as amulets, are also available for purchase at these shrines.

Shinto does not focus on particular moral principles, although it does place a strong emphasis on maintaining purity, mostly through a ceremonial cleansing. Shinto does not have a single founder or doctrinal manuscript, although it does exist in a mix of different and regional versions.

The number of shrines in Japan is divided among the public and also those found in Japanese homes. Counting the home-based shrines are certainly into the millions.

In total there are over 90,000 public shrines. Shinto is Japan’s dominant religion in terms of believers, with Buddhism coming in second. The majority of Japan’s overall population participates in both Shinto and Buddhist practices, particularly festivals (matsuri).

Indicating a prevalent conviction in Japanese society that various beliefs and practices do not have to be incompatible. Shinto elements have also been adopted and mixed into buddhist practices in Japan.

Because there is no universal doctrine or manuscript in Japan, Shinto is harder to describe to outsiders who have never studied the religion.

Shinto has no widely accepted definition. If there is a single general definition of Shinto, it is that Shinto is a belief in kami or the supernatural spirits who are at the heart of the religion.

Shinto History

Shinto did not exist as a specific religion prior to the modern era, but rather as a way of believing. Shinto in the 19th and early 20th century was combined with the imperial government and the emperor himself was seen as kami or a god. Once the war ended in 1945 religion and government were separated.

Perhaps as an attempt to evade the current Japanese separation of religion and state and preserve Shinto’s historical connections with the Japanese state, practitioners prefer to consider Shinto as a “way,” characterizing it as more of a custom or tradition than organized religion.

Shinto was increasingly referred to as a nature religion in the early twentieth century. In Shinto, all things contain kami or spirits in the natural world such as trees, stones, animals, mountains, and even statues.

As a general rule and is sometimes common in Japanese, there is no difference between singular and plural, thus the term kami can apply to both individual kami and numerous kami.

Although there is no exact English equivalent, historians of religion have occasionally translated kami as “god” or “spirit.” other historians say this English translation is deceptive, and a number of Shinto experts advise avoiding translating kami into English.

JAPANS MOST FAMOUS SHINTO SHRINE

The Fushimi Inari Temple, maybe the most renowned Shinto shrine in Japan today owing to its popularity to many photographs online, is a must-see. The temple, which is nestled in southern Kyoto, is known for its long paths of crimson torii gates that connect the shrine’s buildings.

Kami In The Material World

There are eight million kami, according to Japanese belief, and Shinto practitioners accept that they are everywhere. They aren’t considered as all-powerful or immortal as in Christianity, Judaism, or Muslim beliefs in an omnipotent, omnipresent God.

Where is the kami and what is their purpose in nature, the world, and their interactions with humanity?

Kami may be found in both the living and the dead, organic and inorganic materials, and natural catastrophes such as earthquakes, droughts, and pestilence. They can be found in natural elements like wind, rain, fire, and sunlight. Shinto considers “the real manifestations of the universe itself” to be “sacred.”

A Moral Code

If cautions regarding good behavior are disregarded, the kami can cause retribution known as shinbatsu, which typically takes the form of sickness or untimely death.

Some kami, known as magatsuhi-no-kami or araburu kami, are thought to be primarily evil and destructive. Shinto practitioners are aware of these negative kami.

Offerings and prayers are made to the kami in order to earn their blessings and to keep them from doing harm. Shinto aims to foster and maintain a peaceful relationship between people and the kami, and therefore with nature.

Ancestors are regarded as a type of kami in Japanese culture. The enshrined kami of a community founder is referred to as jigami in Western Japan.

Living humans were sometimes regarded as kami, and these were referred to as akitsumi kami or arahito-gami.

The emperor of Japan was proclaimed a kami under the Meiji era’s State Shinto system, and other Shinto sects have likewise regarded their leaders as living kami.

Modern Shinto

How Shinto is practiced today. It is difficult to point to specific directives and how one’s life is lived according to religious doctrine.

Shinto is more interested in traditional practice than theology. Shinto is mostly a ritualistic religion. Shinto rituals are frequently difficult to differentiate from Japanese customs in general, yet Shinto-based ideals and practice are at the heart of Japanese culture, society, and identity.

Tomorrow’s winds will blow tomorrow

Japanese proverb

The Shrine

By the Heian era, many architectural styles of Shinto shrines were largely established. A honden is the inner sanctuary where the kami is said to reside.

Items seen as belonging to the kami, known as shinpo, may be housed inside the honden. Shinpo might include artworks, clothes, weaponry, musical instruments, bells, and statues.

Torii, a two-post gateway with one or two crossbeams over it, marks the entrance to a shrine. There are at least twenty distinct kinds of torii, although the specific features vary. These are said to demarcate the kami’s realm, and going through them is generally considered as an act of purification.

Shinto Practice

Sankei is a general term for a visit to the shrine, whether as part of a pilgrimage or as a regular practice. Hairei is a kind of individual worship performed at a shrine. A visit to a shrine, called in Japanese as jinja mairi, usually takes only a few minutes.

Some Japanese go to shrines on a daily basis, frequently on their way to work. These ceremonies are generally performed outside the Shrine rather than inside it.

The typical method of worship includes a person approaching the Shrine, where practitioners deposit a monetary gift in a contribution box before ringing a bell to summon the kami’s attention. After that, they kneel, clap, and stand while silently praying.

Most large public shrines feature a special rubber stamp seal that visitors or tourists can have printed in their sutanpu bukku (stamp book) to show how many shrines they’ve visited.

The home Shrine

Many Shinto followers have a kamidana, or family shrine, in their houses. In the living area, these are generally shelves set at a raised height. During the Meiji era, kamidana gained popularity. Workplaces, restaurants, stores, and sea ships often have Kamidana.

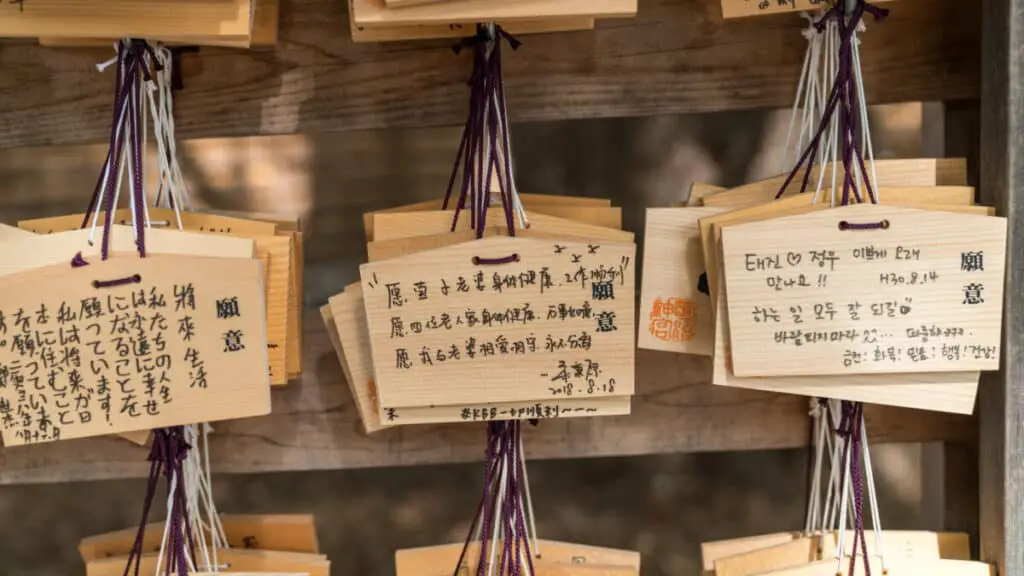

Printed Prayer Plaques

Ema, tiny wooden plaques on which practitioners write a request or desires which they would want to see fulfilled, are a typical element of Shinto shrines. On one side of the plaque, the practitioner’s prayer is printed, while on the other is typically a printed picture or motif linked to the shrine.

Those in charge of the shrine will frequently burn all of the gathered ema at the start of the Japanese new year.

Fortunes Told

The omikuji is a type of fortune that is common at Shinto temples. These are tiny slips of paper that are given at the shrine (in exchange for a donation) and then read their fortune. Those who receive a negative fortune frequently tie the omikuji to a nearby tree or a specially constructed structure.

This conduct is seen as rejecting the fortune, a procedure known as sute-mikuji, and so averting the disaster foretold by the fortunes prediction.

Shrine Festivals

Haru-matsuri are spring festivals that frequently include prayers for a prosperous crops. Ta-asobi rituals, in which rice is ritually sown, are occasionally part of them. Summer festivals are known as natsu-matsuri, and they are generally centered on crop protection from pests and other dangers.

Autumn festivals, called as aki-matsuri, are centered on honoring the kami for the rice or other crops. On November 23, several Shinto temples hold the Niiname-sai, or new rice festival. To commemorate the occasion, the emperor holds a ritual in which he delivers the first fruits of the crop to the kami at midnight.

Winter festivals, known as fuyu no matsuri, focus on ushering in the spring, warding off evil, and bringing in positive influences for the future.

New Years And Shinto Shrines

The new year’s season is known as shogatsu. Shinto Practitioners generally clean their personal shrines on the final day of the year (31 December), omisoka, in preparation for the new year’s day (1 January), ganjitsu.

To commemorate the New Year, many people visit public shrines; this “first visit” of the year is known as hatsumde or hatsumairi.

Public Festivals

Processions or parades known as gyretsu are typical elements of festivals. The kami are move in portable shrines called mikoshi during public processions. Matsuri processions may be chaotic, with many of the participants inebriated. The festivities have a carnival-like feel to them.

Are Japanese Religeous

The majority of Japanese people follow numerous religious traditions. The fact that Japanese individuals frequently respond “I have no religion” when questioned makes determining the percentage of the Japanese population who participate in Shinto activities difficult.

However surveys have shown the following data regarding the Japanese people’s general involvement in religion

less than 40% of the population of Japan identifies with an organized religion: around 35% are Buddhists, 30% to 40% are members of Shinto Shrines. In recent surveys, only 16% expressed belief in the existence of kami in general.

Perhaps the festivals and activities of the Japanese within Shinto are more cultural tradition rather than religious devotion.